"Pumping Iron" the movie that changed opinions

In the 1970s, a new breed of American man emerged from the weight rooms of Gold’s Gym in Venice Beach. Led by Arnold Schwarzenegger, a clique of world-class bodybuilders – muscle-bound, steroid-fueled, bronzed like suntanned gods – pumped iron, chased girls, and changed the world’s exercise culture forever.

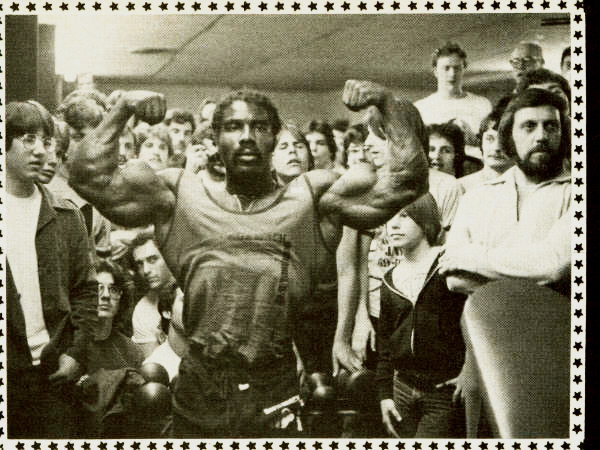

Robby Robinson, a wedge of black marble, arrived in Venice Beach in 1975 with one oversize suitcase and seven dollars. That was every dime he had after quitting his job and selling everything of value but the trophies he’d won at bodybuilding shows in the Jim Crow South. He’d left behind a wife, three small children, and a certain localized fame as the best-ever body in the state of Florida, fronting 20-inch biceps, a 28-inch waist, and 205 pounds of peaked, freak muscle on his hourglass, 5-foot-8 frame. But if your dream back then was to make the cover of ‘Muscle Builder’ and storm the palace of giants in your sport, there was one thing to do and one place to do it: Join Gold’s Gym in Venice Beach. With the ocean at its back, the sun through its skylights, and the biggest men on Earth trooping in by the dozen to bench 450 before breakfast, Gold’s was Camelot-by-the-shore. You felt its pull in your hypertrophied heart, deep in the belly of that reckless muscle.

Robinson, born and raised in the swamps of Tallahassee by an illiterate mother and a bootlegging father who later abandoned his 14 children, had a deep and perfectly rational terror of whites. Driving to shows in Mississippi and Georgia, he had seen the signs posted on rural light poles: ni**ers, don’t get caught here come sundown. But it was a letter from a white man that had brought him to Venice: a written invitation from no less than Joe Weider, the publisher of Muscle Builder, to come out and join his stable of champion bodies living and training large in Los Angeles. Robinson got off the plane expecting to be met by Weider, or if not by him then by Arnold Schwarzenegger, Weider’s Austrian prince, who’d won the title of Mr. Olympia five times running. Neither showed up, though, and after standing around for hours, Robinson tossed the suitcase over his shoulder and walked nine miles to Venice in platform heels.

Robinson, born and raised in the swamps of Tallahassee by an illiterate mother and a bootlegging father who later abandoned his 14 children, had a deep and perfectly rational terror of whites. Driving to shows in Mississippi and Georgia, he had seen the signs posted on rural light poles: ni**ers, don’t get caught here come sundown. But it was a letter from a white man that had brought him to Venice: a written invitation from no less than Joe Weider, the publisher of Muscle Builder, to come out and join his stable of champion bodies living and training large in Los Angeles. Robinson got off the plane expecting to be met by Weider, or if not by him then by Arnold Schwarzenegger, Weider’s Austrian prince, who’d won the title of Mr. Olympia five times running. Neither showed up, though, and after standing around for hours, Robinson tossed the suitcase over his shoulder and walked nine miles to Venice in platform heels.

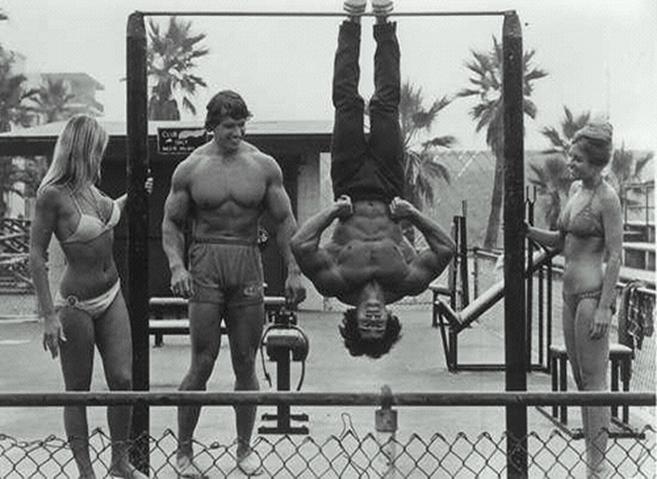

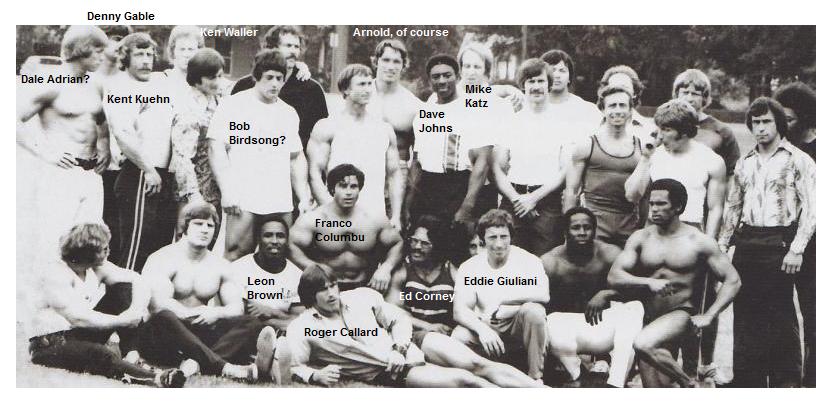

He found a place to crash at a fellow bodybuilder’s and showed up at Gold’s one morning that spring, gawking through the window, dumbstruck. “I couldn’t bring myself to train. I was so in awe. All my idols in one room! Arnold and Denny Gable, Bob Birdsong and Franco Columbu; these beasts working out with no shirts or shoes and a crowd of people watching from the street.” The gym manager, Ken Waller (a Mr. America and Mr. Universe), saw Robinson hulking by the door. “You,” he growled. “You wanna train here? Fine: Come lift what we lift.” He pointed to a pair of humongous dumbbells, 150-pounders with tapered grips. “Get down on that bench and give me 10,” he said. “Otherwise, get the fuck out and stay out.” Robinson, who’d built himself in backwoods gyms, had never seen dumbbells half so big. Somehow he got them onto his thighs, then, trembling, winched his back down on the bench. Each rep was a carnival of toil and pain, the weights teetering as they went up and ticked back down, the fibers of his mid-pecs shrieking. “I’ve no idea how I did that set,” says Robinson, now 65 and still wondrously carved, his traps and triceps bulking through a linen shirt, his waistline waspish as ever. “But the adrenaline going through me then, that drive to be one of them – it was like a double shot of steroids and B-12.” He fought the 10th rep up, screaming and twisting, then dropped the weights on the concrete floor. “You’re in,” grunted Waller. “You’re one of us. Now go and give me a dead lift of 700.”

Muscle, in all its meanings, is such a deeply American trope that it feels like part of our national narrative. We’ve made strength the flag of our exceptionalism and believe, however vainly, that our might will prevail in any test of wills against our foes. We’ve even found a way to monetize muscle, building an industrial complex of health clubs and home gyms and their hugely lucrative sideline: nutritional supplements. Thirty years ago, men stopped at a bar for a cold one after work; now those bars are Ballys and Crunches, and the person sweating beside you is as likely to be a woman as the guy who used to buy the second round. Most of them aren’t there to build contest-quality mass or prepare for strongman shows; they go in pursuit of fitness, which is strength by another name – muscle fit for stock traders and internet geeks.

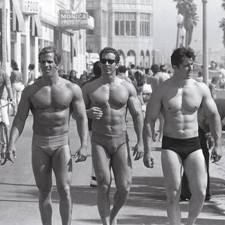

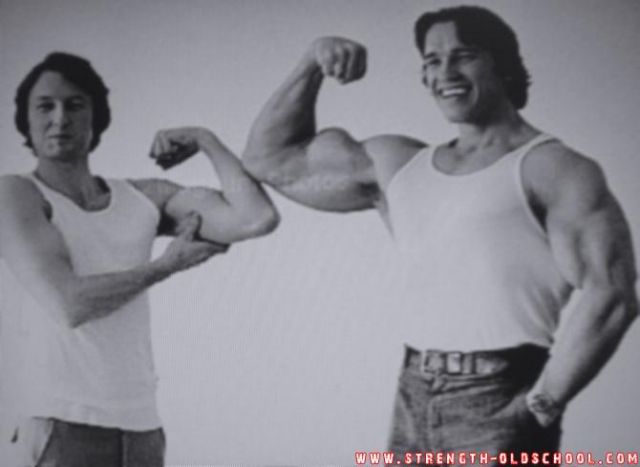

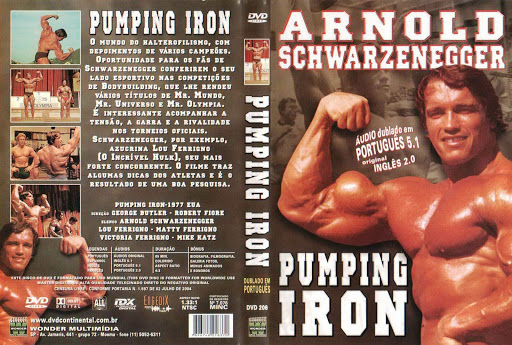

But if you were born anytime after the release of ‘Conan the Barbarian’ in 1982, it may shock you to learn that as late as the 1970s, Americans were repelled by the sight of brawn. “I’d go to the beach, and they’d give me the wolf whistle, guys on a blanket wanting to fight,” says Eddie Giuliani, the 1974 Mr. America (short division) and one of the early legends at Gold’s. “Nobody liked guys with the lumps back then. They thought we were all morons and fairies.” George Butler, codirector of ‘Pumping Iron’ – the landmark documentary that made a rock star of Schwarzenegger and almost single-handedly changed America’s view of well-built men – says, “I always liked to walk behind Arnold in the street so I could check out people’s reactions as we passed. They’d point at him and sneer: ‘God, look at that fucking freak. What a clown.’”

But if you were born anytime after the release of ‘Conan the Barbarian’ in 1982, it may shock you to learn that as late as the 1970s, Americans were repelled by the sight of brawn. “I’d go to the beach, and they’d give me the wolf whistle, guys on a blanket wanting to fight,” says Eddie Giuliani, the 1974 Mr. America (short division) and one of the early legends at Gold’s. “Nobody liked guys with the lumps back then. They thought we were all morons and fairies.” George Butler, codirector of ‘Pumping Iron’ – the landmark documentary that made a rock star of Schwarzenegger and almost single-handedly changed America’s view of well-built men – says, “I always liked to walk behind Arnold in the street so I could check out people’s reactions as we passed. They’d point at him and sneer: ‘God, look at that fucking freak. What a clown.’”

Gold’s Gym didn’t blow that bias away the day it opened for business in 1965. But in less than a decade, it became the Athens of muscle, the cradle of a full-blown body culture and the place where the gods of iron inspired millions. Everything we have now, from moonshot-hitting shortstops to film stars busting out of their bandoliers, began in that no-frills bunker by the beach. Joe Gold, the ornery seaman who built the place and has since been largely forgotten, had a lot of timely help from other people, not least of them Butler, whose charismatic film spread the Gospel of Huge to a scrawny nation. None of that would have happened, though, without Gold’s vision. He made a space where titans congregated.

Gyms in the 1960s were scarce and vile, most of them unfit to train a dog. When Gold’s opened its doors on Pacific Avenue in Venice, there were only three other clubs serving 7 million people in Los Angeles, and one of them, the Dungeon, was so unsavory that even powerlifters left their wallets at home. There was next to no money in the major competitions – Mr. Olympia, the top show at the time, paid $1,000 to the winner (Phil Heath, the 2011 winner, earned $600,000) – and the stars of this firmament worked knuckle-

dragging jobs just to earn enough to train. (Schwarzenegger and Franco Columbu, a future Mr. Olympia, took bricklaying gigs; Lou Ferrigno carried caskets at a mortuary in Brooklyn and lived with his parents well into his 20s.) Bodybuilding was beached on the far shores of pop culture, poking along, barely in the muscle zines, which existed to sell barbells to skinny teens. “They had smallish circulations,” says Wayne DeMilia, a masterful promoter who raised the sport’s profile in the 1980s by turning tournaments into sex-bomb pageants. “Weider earned off his products, the equipment, and protein powders.” DeMilia, who left the sport in 2004 after Weider sold the business, by then a media empire, for $350 million, adds, “If you were one of his boys, he’d give you free ad space to hawk your own mail-order crap. That’s how Arnold made his first money, selling exercise booklets to kids.”

Gold’s Gym was a money pit from the day it opened until Joe Gold sold it in 1970; it seemed Gold went out of his way to avoid making a buck. He’d built a two-story bulwark of concrete blocks that had all the amenities of a morgue – a place exclusively for hardcore lifters, many of them friends of his from boyhood. The gym was big for its day, 30 feet wide and 100 deep, and consisted of a single, large, double-height space, unlike the rabbit-hutch layouts of other gyms. Up a narrow staircase was a smallish loft where members could change and shower after workouts or dose themselves with the first, crude anabolics – typically, Dianabol tablets and Deca-Durabolin shots, a combo that grew muscle but also compromised heart walls (as these men would come to regret in middle age). The gym’s windows were sealed, there was no sign on the facade, and Gold usually kept the front door locked, lest any casual lifters happen by. “You’d go in the back door, which was always propped open – that way we’d get the breeze from the ocean,” says Ric Drasin, a pro wrestling legend in the 1970s and ’80s who joined Gold’s Gym in 1969. “You could park back there, but most of the guys walked. They could barely afford rent, let alone gas.”

Gold kitted the place out with equipment he’d forged himself in the shop behind his house: signature dumbbells with tapered grips that snugged perfectly in your palm and reinforced benches with closely set stalks that you could push against for leverage in heavy sets. He’d also had the foresight, or dumb luck, to install a bank of skylights in the roof, and the flood of natural light brought photographers down in droves to shoot the half-clad bodybuilders. “There was no heat or A/C, and you could really freeze your ass there in the winter,” says Drasin. “We’d go to Joe and bitch, and he’d say, ‘So put some damn clothes on,’ because guys would train in tiny posing trunks.”

Gold had no patience for complainers; he made gladiators, not big-armed girls. The son of a Jewish junkman, he’d grown up in the working-class slums of L.A., and he had learned to fight his battles when the Polish toughs hassled him after school. In high school, he began hanging around the Muscle Beach Weight Pen, where the giants of the day posed for boardwalk crowds that grew to the tens of thousands on weekends. Gold got big there and formed lifelong friendships, and though he was gone for long chunks of the next two decades – to the South Pacific in World War II, where he was injured by a torpedo strike, and to South America with the Merchant Marines until he quit sailing in the early 1960s – his heart was firmly docked off Muscle Beach. When the authorities shut the Pen down in 1959, declaring it a magnet for “low morality” (read: big bodies, small swimsuits, horny tourists), Gold’s friends scattered to dives like the Dungeon and a new, bare-bones weight pit on Venice Beach. Gold built his gym to bring those beasts home, and charged them the sweetheart rate of $40 a year. “If you didn’t have the cash, though – and a lot of them didn’t – Joe would let you slide,” says Drasin. “Hell, at some point or another, he supported half those guys. Paid ‘em to show up and do nothing.”

The great ones enrolled, and the grotesques did too – the split seemed to run about 50-50. Among the former was Dave Draper, the surf-tanned Mr. America whose presence on Weider’s magazine covers was a clarion call to bodybuilders, and mighty Steve Merjanian, an Armenian strongman who benched 500 pounds for fun. Then there were the wackjobs whose fixed compulsions would have gotten them ousted from other gyms. They included Bob Schott, who’d leave between sets and punch the walls outside until he bled; a huge German named Yogi, garbed head to toe in SWAT gear, who boasted of blowing more than 100 Marines a day in the park behind Camp Pendleton; and Bugsy, who dressed like a Chicago gangster and drank a fifth of vodka while he trained. “So many nuts there,” says Drasin. “Then Arnold got famous and was on the cover of every mag. That was when the real fun started.”

At 21, Schwarzenegger was in the first wave of muscle migrants who landed on Gold’s doorstep in 1968. An eye-popping but unpolished hulk with step-by-step plans for world domination, he had been dreaming of America since the day he started lifting as a teen in Graz, Austria. Ill-treated by his father, a policeman and former Nazi who shamed and beat his son for small infractions, he had erected his self-conception in darkened theaters, watching his idol Reg Park, Mr. Universe in 1951, play Hercules, crushing zombies with giant boulders. He’d bike eight bumpy miles to a village gymnasium to work out, training with such fixity that he went AWOL in the army to compete for Junior Mr. Europe in 1965. (He returned with the title – and earned himself a week in the brig.) He consolidated his legend the following year, winning Mr. Universe at age 20, the youngest ever to do so. Though smooth through the middle – he lacked the muscle separation commonly found in veteran bodybuilders – he had the bearing of a king when he took the stage, and exploded as he hit his poses. “The great ones have this trick of growing before your eyes,” says Randy Roach, the author of ‘Muscle, Smoke & Mirrors,’ bodybuilding’s definitive history. “Arnold was a master at shocking the crowd. He trained their eyes to want more.”

At 21, Schwarzenegger was in the first wave of muscle migrants who landed on Gold’s doorstep in 1968. An eye-popping but unpolished hulk with step-by-step plans for world domination, he had been dreaming of America since the day he started lifting as a teen in Graz, Austria. Ill-treated by his father, a policeman and former Nazi who shamed and beat his son for small infractions, he had erected his self-conception in darkened theaters, watching his idol Reg Park, Mr. Universe in 1951, play Hercules, crushing zombies with giant boulders. He’d bike eight bumpy miles to a village gymnasium to work out, training with such fixity that he went AWOL in the army to compete for Junior Mr. Europe in 1965. (He returned with the title – and earned himself a week in the brig.) He consolidated his legend the following year, winning Mr. Universe at age 20, the youngest ever to do so. Though smooth through the middle – he lacked the muscle separation commonly found in veteran bodybuilders – he had the bearing of a king when he took the stage, and exploded as he hit his poses. “The great ones have this trick of growing before your eyes,” says Randy Roach, the author of ‘Muscle, Smoke & Mirrors,’ bodybuilding’s definitive history. “Arnold was a master at shocking the crowd. He trained their eyes to want more.”

About the only one capable of stopping Arnold was Arnold. He had a lot of rage he hadn’t worked through and kept his nights free to act it out, brawling in beer halls and railway stations, acting the overblown bully. The cops in Munich, where he ran a small gym, made it clear they wanted him gone, and in 1968, he leaped at a contract offer from Weider to train in California and pose for pictures. His arrival later that year was muscle’s Big Bang moment: the expansion of the sport around a superheated star with the size and charm to seduce the world.

Gold’s was already a beacon to serious bodies in lonely iron outposts around the world; it showed up almost monthly in Weider’s magazines, and was well known to bodybuilders in Europe, who’d seen it in foreign knockoffs of ‘Muscle Builder.’ But Arnold upped the stakes just by walking through the door; the ferocity he brought to a routine set of leg curls lit everyone’s pilot light. “He’d kill himself getting the last five reps, to the point he was pouring sweat and could barely stand,” says Drasin. “Then it was your turn, and he’d make you do it. It was like an insult if you didn’t match his count.” “Nine-thirty, sharp, he’d walk through that door, and everyone threw more plates on the bar,” says Giuliani. God forbid Arnold caught you not working out, or fibbing about the work you’d put in. “He’d ride you all day, and the day after, too,” adds Giuliani. “Arnold saw everything, and he didn’t forget.” The intensity he fostered crept pretty close to madness, and it became the new standard at Gold’s. “Guys fainting after squats, guys throwing up in the alley; he was at a whole other level,” says Giuliani.

A retinue quickly formed around Arnold, a clique of the best bodies on Earth. There was Columbu, Arnold’s best friend from Europe and his immediate successor as Mr. Olympia – they’d met at a weightlifting tourney in Munich, where Columbu, only 5-5, gob-smacked the crowd by doing rep-set squats of 400 pounds. Waller, an ex–tight end who’d played for Western Kentucky, was a block-of-granite redhead who’d go on to win every major but Mr. Olympia. Giuliani, the lightweight champ who’d moved his family from Brooklyn in 1969, functioned as Arnold’s Italian uncle, bringing him home to gorge on cannelloni and tease his preteen daughters. Roger Callard, a Mr. America, was the Adonis of the crew, a 5-9 slab of girl bait who went on to work in pulp movies; and Drasin, a blond hellion from Bakersfield, California. Bull-chested strong – he benched 21 reps of 320 pounds – Drasin was also a crackerjack mimic, endearing himself to Arnold with drop-dead impressions of the menagerie at Gold’s. “We clicked with each other because we liked to have fun, at least between October and March,” says Drasin, referencing the period after contest season, when Arnold took his training down a notch. They’d crack on Columbu, whom Arnold called “the champion of junior high,” and rib Giuliani, a proud Sicilian, about his wife running around with black bodybuilders. Then there were the mobs of neophyte lifters who pressed Arnold for workout tips. “He told this joker who asked about diet to dump salt on all his food, and the guy did it and wound up in the hospital,” says Drasin. Another one asked about contest poses; Arnold took him to the locker room and smeared him with motor oil, said it was the “latest thing in Europe and made your abs pop.” Then he had him scream as he posed, and the guy came down and did it for the crew. “We tried our best to keep a straight face, but all of us fell out laughing,” says Drasin.

Wherever Arnold went, his Rat Pack followed; he rolled eight-deep, even to breakfast. It was Zucky’s Deli for the first of their morning meals – five-egg omelets and mounds of cottage cheese – then the Jamaica Bay Inn for one of the day’s steaks and baked potatoes. Arnold ate with care, shunning cake, bread, and pasta until his weekly Saturday-night apple-pie pig-out, and rarely gained more than five or 10 pounds after the season ended.

There was no such check on his other hungers, though: He loved women, and he loved them in bulk. “We’re in this bank line once in Venice, and he’s making eyes at the teller, a big old girl with a huge ass,” says Dan Howard, a Mr. America entrant who managed Gold’s Gym for four years. “Arnold says, ‘You haff nice breasts; now please to turn around…. Ah, yes, I like your backside. Take my phone number.’” Another time, Arnold brought a generously rumped skier to dinner at a crowded steakhouse. “He says to me, ‘Watch this,’ and throws her dress over her head; sure enough, she’s wearing no panties,” says Howard. “She runs sobbing from the place, then comes back in and says he told her not to wear any.” Drasin remembers feasting with Arnold at Donkin’s Inn, a dive bar and dance joint in Marina del Rey, where the crew had the run of big-haired girls who drove in from the Valley on weekend nights. “They’d come over and grab our pecs and say, ‘Are those things real? How do you get ‘em so big?’” There were parties at the place Arnold shared with Columbu, orgies at a Venice bungalow, and a nightclub stocked with beach girls that Waller ran as a kind of private reserve. Often enough, they didn’t have to leave the gym; women wandered in from the nude beach in Venice, wanting a private tour of the lockers. “They got it, too,” says Drasin, “though it wasn’t unheard of to bang ‘em right there on the gym floor.”

Gold loved his gym, but he ran it like a Moose Lodge, a bare-walls clubhouse for his cronies. He never bought ads in the L.A. papers and wouldn’t even list Gold’s in the Yellow Pages, perhaps because he hadn’t installed a phone. (There was a pay phone near the door, but it was for members’ use only.) If Gold’s was ever to be more than a cultural footnote, someone else was going to have to grow the brand, push it as a lifestyle for novice lifters. Gold got out of the way when he sold the gym in 1970 and headed back to sea as a commercial sailor. A number of his friends and members, though, defected to other gyms, and it wasn’t long before the two men who bought the place, bleeding money, started looking to unload it or shut it down. Enter Ken Sprague, showman nonpareil and the first to hatch a business plan for gyms. In two years, he would turn Gold’s into a cash machine – and look the other way when some of his brand-name bodybuilders turned it into a roaring whorehouse.

Sprague had discovered Gold’s while vacationing in California in the summer of 1969; he’d sneaked in to train when the manager was out to lunch and was struck by its beauty and strangeness. “The way the light hit it and the smell of the ocean – it was the opposite of every gym I’d ever been in,” says Sprague. He moved west the following summer and enrolled at Gold’s, hoping to craft a bigger life than the one laid before him in Ohio. He’d been a track-and-field star at the University of Cincinnati and a promising bodybuilder who won Mr. Cincinnati at the age of 22. But he’d married young, quickly fathered a son, and needed to earn real money fast. He’d come to the right town for that: L.A. teemed with options for well-built men. Sprague had signed with Colt Studios under the stage name Dakota, and launched a very profitable shadow life, posing for gay calendars and ‘Blueboy’ stroke books, and even acting in occasional porn films.

Sprague quickly amassed both a fan base and a grubstake; by 1972, he had enough money in the bank to make a down payment on Gold’s. “Anyone could have bought it for 15 grand up front, but no one had the cash or the desire,” he says. “All I wanted was to keep the place going. There was nowhere else I could even imagine training.”

Soon after he bought the gym, Sprague upped its cachet by sponsoring muscle contests that fetched big crowds, paying Waller and Schwarzenegger 50 bucks apiece to guest-pose before the judging. Buoyed by the turnout, Sprague began promoting the Mr. America tourney, which typically drew just a few hundred fans and paid no prize money to the winner. Sprague staged the event as a three-ring circus, leading a parade of half-clad bodybuilders riding bull elephants to the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, while brass bands played and a plane flew overhead trailing a banner trumpeting Mr. America, and, of course, Gold’s Gym. He sold 6,000 tickets and offered the top-tier patrons the chance to personally oil up a contestant.

Sprague would earn a second fortune creating and staging shows, adding the Gold’s Classic and Mr. California to the contest season. His masterstroke, though, was hawking products that no gym owner before him had thought to sell. He printed Gold’s T-shirts (with a logo designed by Drasin) and asked the crew to wear them during shoots. They sold faster than he could mail them, in the tens, then hundreds, then thousands, a cash tsunami that wouldn’t quit. “They certainly did better than my first idea, which was selling used pairs of Arnold’s briefs,” says Sprague.

Suddenly, there were stories in the L.A. papers about the swinging new trend of pumping iron and celebrity sightings at that hot spot, Gold’s, with stars like Clint Eastwood, Jane Fonda, and Muhammad Ali dropping in to train. Gays stopped by, too – a natural development; they made up much of the audience for muscle mags. Since the 1950s, when Weider printed soft-core titles aimed at young gay readers (‘Adonis, Body Beautiful’), the sport had quietly wooed that demographic while denying it at the top of its lungs. There was plenty of denial going on at Gold’s, too. There were men who joined solely to befriend the bodybuilders and offer them quid pro quo: At least half a dozen were doctors who swapped steroid prescriptions for a comprehensive menu of sexual favors. Sprague knew about the johns hanging around the bodybuilders, but decided to live and let live. He even helped members catch on with Colt Studios, hooking up a number of prominent bodybuilders for skin flicks and nudie shots. “Not everyone did it, but the list of guys who did would cover every title,” he says. “Up to and including Mr. Olympia.”

Calls would come in on the pay phone at Gold’s from people seeking to book a “model” for a shoot. Limos would pull up in the alley out back, and world-famous bodybuilders would split for an hour, then return to finish their hack-squats. “We had some tense moments, given the macho reputations of the guys who were hustling,” says Sprague. One time he overheard a former Mr. America being taunted by his buddies for booking dates. “He yelled, ‘Well, I certainly don’t kiss them!’ ” Sprague says, then adds, with a laugh, that the taunters were often up to their necks in whoring, too.

Over the years, whispers have circled about Arnold’s possible involvement in the gay-for-pay cash grab at Gold’s, but no evidence has ever emerged. Sprague, when asked, says he had no direct knowledge and wouldn’t comment on rumors. So, too, with Drasin and the others I talked to, who conceded that Gold’s was rife with hustlers, but not them and surely not Arnold. Efforts to reach Schwarzenegger were unsuccessful. I couldn’t ask him, then, about that other vice at Gold’s: the prolific, and very public, use of steroids. “You had to be smart when you emptied the trash: There were needles poking out of the cans,” says Sprague. “We all did the basics like Dianabol and Winstrol, but Arnold had the better drugs from Europe,” says Drasin. “Primobolan, Bolasterone, stuff you couldn’t get here. They made you not just bigger, but crazy strong.” No one had to hunt and peck for a source, either: Mexico’s farmacias were two hours south, every shelf stocked with prime gear. If you didn’t want to truck with Gold’s doctors for a scrip, there was a Beverly Hills pediatrician on call. “You’d sit in his office and there’d be moms and kids on one side and big, sweaty guys on the other,” says Robby Robinson.

You can track the changes in the layouts of Weider’s magazines. The men in those 1970s spreads were bigger and sharper than their counterparts 10 years prior, eclipsing the Dave Drapers and Larry Scotts and foretelling the fright-show hulks a decade later – the Lee Haneys and Gary Strydoms who were so enlarged that Weider started a magazine just for them, padding ‘Flex’ with ads for “nutritional products” that hinted, or in some cases screamed to the heavens, that they were just like steroids. You can also mark the damage that the needle did to a very broad cohort of 1970s bodybuilders. Denny Gable, a core member of Arnold’s crew, had a heart attack and died at age 49. Paul Grant, a Mr. Universe and Gold’s regular, succumbed to kidney failure at 60. Mike Mentzer, another Mr. Universe and the heir apparent to Arnold, dropped dead of heart failure at the age of 49, after battles with addiction and psychosis. His younger brother Ray, a Mr. USA, died two days later of kidney failure. A frayed thread divides them from the lucky survivors, who share a raft of strikingly similar ailments. Schwarzenegger had heart-valve surgery at age 49 to repair – ahem – a congenital defect. Draper and Mike Katz, both Gold’s Gym fixtures, have had major heart procedures. And Drasin, 67, has ventricular hypertrophy and has had to take blood thinners that leave him bruised and weak. If he had it to do over, though, he wouldn’t change a thing. “Everything I’ve ever gotten, it started there,” he says. “However long I have, I’ve lived enough for two lives – and I’ve got the pictures to prove it.” Lets put in perspective, every one dies, if you used steroids or not. During the golden age of bodybuilding, the guys used much smaller amounts. Scientific research showed no increased mortality rate of these guys (under this blogpost).

Sprague had built something epic at Gold’s – now all he needed was a Homer to come along and immortalize the gym for the ages. In 1974, he got a call from a freelance photographer named George Butler. Butler and his partner, the novelist Charles Gaines, had flown out to Venice a couple of years earlier to research a book about bodybuilders. Though superbly written and shot, it was spiked by its editor, who said it would be a laughingstock with critics. A second house reluctantly published ‘Pumping Iron,’ which went on to be a smash bestseller and critical darling. Now Butler hoped to make a film on the subject, but was having doors slammed in his face. Friends and family mocked him even after the book took off, and he’d had to borrow money to make a test film of Arnold to screen for potential investors. One of them, the playwright Romulus Linney, stood up and spoke for the crowd: “You must know the truth, George. If you put this Arnold Schwarzenegger onscreen, you and he will be laughed off 42nd Street.”

But in Arnold, Butler saw a walking work of art and the discovery of his very young career. He hit on an ingenious ploy to raise money: display Arnold and his peers as living sculptures. Butler booked the auditorium at the Whitney Museum, put Schwarzenegger and Waller on rotating disks, and invited the fine-art media to critique them. A few hundred fans were expected to show; instead, 5,000 people pushed through the ropes, and when their money couldn’t be stuffed into the registers, attendants simply piled it on the floor. Butler netted enough to begin production, but first he had to talk his tent-pole star out of an early retirement. Arnold, Mr. Olympia for five years running, had declared himself done with all that bother and was ready to try his hand at acting. “But I assured him that the film would kick that off, be his calling card at every studio,” says Butler. For that, and for $50,000, Arnold agreed to take part in the 1975 Mr. O show; alas, the money Butler gave him left little to spend on location fees. Sprague, always alert to a marketing coup, invited him to use Gold’s Gym free of charge.

The monthlong shoot went well, by and large, though the bodybuilders not included were furious at Butler and kept lumbering into the frame. Ditto the cast members not named Arnold: They were irked that he was being paid grandly by Butler while they couldn’t even get a day rate. “I said, ‘You gotta throw us something,’ so he gave us worthless contracts, plus $100 a day to feel better,” says Robinson. “Then even that stopped, and we never saw no back-end. The only ones who earned were him and Arnold.” Those beefs notwithstanding, Butler’s hunch was vindicated: The sport, and its characters, were high theater. There was Arnold, the swaggering serpent king running head games on his contest rivals; Katz, the sensitive hulk from New Haven whose sanity seemed to hinge on winning a title; and Ferrigno, the desperate-to-please deaf kid who almost stole the movie from Arnold. Taunted and emotionally abused by his father, Matty, a domineering New York City police lieutenant, Ferrigno was a latter-day Samson in chains, fighting for his freedom in every scene. The two-time Mr. Universe had recently quit the sport and “moved to Ohio to get away from my father,” says Ferrigno. “I knew I wouldn’t win if I did the film; there was only eight weeks left to train for the show.” But Matty, convinced the film would make him a star, prevailed on Lou to take one for the team. His father’s performance as the doting, koan-spouting stage dad was one of the creepier enactments in modern film, and cast Lou as the mute, antagonized giant who might snap at any moment and burn the temple. Arnold mocked him on camera as a docile child, but he was much more humane behind the scenes, telling Ferrigno “to make the sign of the cross every day you’re away from that man.”

The monthlong shoot went well, by and large, though the bodybuilders not included were furious at Butler and kept lumbering into the frame. Ditto the cast members not named Arnold: They were irked that he was being paid grandly by Butler while they couldn’t even get a day rate. “I said, ‘You gotta throw us something,’ so he gave us worthless contracts, plus $100 a day to feel better,” says Robinson. “Then even that stopped, and we never saw no back-end. The only ones who earned were him and Arnold.” Those beefs notwithstanding, Butler’s hunch was vindicated: The sport, and its characters, were high theater. There was Arnold, the swaggering serpent king running head games on his contest rivals; Katz, the sensitive hulk from New Haven whose sanity seemed to hinge on winning a title; and Ferrigno, the desperate-to-please deaf kid who almost stole the movie from Arnold. Taunted and emotionally abused by his father, Matty, a domineering New York City police lieutenant, Ferrigno was a latter-day Samson in chains, fighting for his freedom in every scene. The two-time Mr. Universe had recently quit the sport and “moved to Ohio to get away from my father,” says Ferrigno. “I knew I wouldn’t win if I did the film; there was only eight weeks left to train for the show.” But Matty, convinced the film would make him a star, prevailed on Lou to take one for the team. His father’s performance as the doting, koan-spouting stage dad was one of the creepier enactments in modern film, and cast Lou as the mute, antagonized giant who might snap at any moment and burn the temple. Arnold mocked him on camera as a docile child, but he was much more humane behind the scenes, telling Ferrigno “to make the sign of the cross every day you’re away from that man.”

Butler wrapped shooting in 1975, then begged and scraped to finish postproduction. All he had to air, though, was a single print of ‘Pumping Iron’ and not a dime to distribute or promote it, so he pleaded with his stars to attend the New York screenings and strip down and pose after the credits. “I’d come through the curtain and the place would go bananas, gay guys and housewives up cheering,” says Ferrigno. “It was this really fancy theater at the Plaza Hotel, and they’d walk out sweaty, like they’d seen the Chippendales. But the word got out, and it became a hit. Packed ‘em in solid for 10 weeks.”

Fewer than a million Americans ended up seeing it that year, though it did well in overseas sales and returned to air regularly in the 1980s and ’90s on broadcast and cable stations. But its release started a cultural brush fire that very quickly overleaped containment. Arnold became a movie star, booking three films before his breakthrough hit, ‘Conan the Barbarian,’ in 1982. Ferrigno was cast as the Hulk in 1977, a role for which he is still famous. Mainstream actors caught the bug – Clint Eastwood was jacked and shirtless in ‘Every Which Way But Loose’ (1978); Sly Stallone and Carl Weathers were ripped to shreds for ‘Rocky II’ (1979) – and Gold’s was suddenly featured in fashion rags and in an admiring piece on 60 Minutes. Sprague’s membership, less than 100 when he bought the place, blew up to 1,400, and the dues he charged more than tripled, to $200 a year.

But when his second wife fell ill and died of cancer at the age of 27, Sprague lost his heart for the business. He sold it in 1979 and retired, at 34, to an island off the coast of Washington, where he raised his two sons and took postgrad courses in evolutionary biology. His buyers did well, though, riding the spandexed fitness boom to open a line of Gold’s Gyms in the 1980s. Currently owned by a company based in Irving, Texas, the chain boasts 600 clubs in 30 countries, and its flagship branch, just blocks from the original, is America’s high cathedral of stylized mass. The size of two football fields, it has one-of-a-kind amenities including a posing room with bleachers, an outdoor weight pen for strongman training, and wall after wall of larger-than-life posters of the men who built the brand: Arnold and Franco, Lou and Robby, Draper and Giuliani. Conspicuously absent, however, are tributes to Sprague and Joe Gold, or Gaines and Butler, for that matter. “I joke that ‘Pumping Iron’ had more cash flow than ‘Star Wars,’ because it opened up 100,000 gyms,” says Butler, who has since made half a dozen films, including ‘Pumping Iron II: The Women.’ “We came into a sport that was ripe for translation, and we did it, and I’m glad we did. I just wish that Gold’s would acknowledge that fact: start a Hall of Fame and put us in it.”

Butler is right: The lords of Muscle Beach should be exalted in a proper installation. All they did was change everything, birthing the body culture of the 1980s and ’90s and redrafting the desired male physique. But Arnold aside, none of those iron titans, sadly, earned anything like their due, patching together livings as trainers and bouncers and showbiz hangers-on. In a just world, Robert Rowling, Gold’s billionaire overlord, would buy the site of the original gym and remake it into muscle’s place d’honneur. Along one wall there’d be a replica set of Joe Gold’s priceless dumbbells, which were sold as scrap, for five and 10 bucks, by the men who bought the gym from Sprague. In the gallery, beside life-size bronzes of the Greatest Generation of bodybuilders, you’d see animatronic castings of the body parts for which they were rightly famous. There’d be Columbu’s enormous thighs, the abductors bunched like pythons; Robinson’s gull-winged upper lats; and Schwarzenegger’s unmatched chest and arms, a torso from Alpha Centauri. Those men put a health club on every corner, and made it safe to bare your guns in public. Give praise, and your donations, at the door.

Article by Paul Solotaroff

******************************************************************************

Top athletes live just as long as ordinary people despite steroid use.

During the sixties and seventies steroid use was not controlled, so wrestlers, power lifters, weight lifters, shot putters and javelin throwers – if they wished – could inject as much as they wanted. And although quite a few of them did just that, it had no effect on their life expectancy, researchers at the University of Gothenburg report in the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports.

During the sixties and seventies steroid use was not controlled, so wrestlers, power lifters, weight lifters, shot putters and javelin throwers – if they wished – could inject as much as they wanted. And although quite a few of them did just that, it had no effect on their life expectancy, researchers at the University of Gothenburg report in the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports.

Cyclists who participate in the Tour de France live six years longer than the average male, despite the intensive use of performance-enhancing drugs that is prevalent among professional cyclists. Cycling is a typical endurance sport. But what about sports where maximal strength and explosive strength are paramount? Wrestlers, power lifters, weight lifters, shot putters, and discus and javelin throwers are also fans of illegal performance enhancing substances. Do they also live longer than ‘normal’ humans? Or is their life expectancy shorter?

A scientific literature search reveals exactly one study that answers this question. [Int J Sports Med. 2000 Apr;21(3):225-7.] In 2000 epidemiologists at the Finnish National Public Health Institute published a study in which they calculated that the mortality risk of elite power lifters was almost five times as high as that of the rest of the population.

A scientific literature search reveals exactly one study that answers this question. [Int J Sports Med. 2000 Apr;21(3):225-7.] In 2000 epidemiologists at the Finnish National Public Health Institute published a study in which they calculated that the mortality risk of elite power lifters was almost five times as high as that of the rest of the population.

The size of the study was small, however. The researchers collected data on just 62 power lifters, most of whom had probably used steroids. The Finns also only managed to follow the power lifters for twelve years.

We can improve on that, the Swedes thought. They gathered data on nearly 1200 athletes, all of whom did power sports during the sixties and seventies. The researchers discovered that in this group 20 percent of the athletes admitted to having used anabolic steroids. [Br J Sports Med. 2013 Oct;47(15):965-9.] The actual percentage of users was probably higher.

The Swedes followed these athletes for 30 years. For this period there was hardly any difference between the mortality rate of the athletes and that of the Swedish population as a whole, as the figure below shows.

- Login to post comments