Meldonium

There are always new compounds that are used as a PED (performance enhancing drug), because the financial interests in elite sports are huge. This is not true in the case of Meldonium. In fact Meldonium is used in elite sports by Russian and Eastern Bloc countries for many, many years to improve recovery. And that’s why it was banned, because mainly this select group of nations used it.

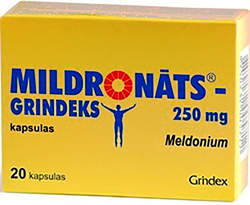

Meldonium, which is sold under the brandname Mildronate, is manufactured in Latvia by the company Grindex. It has been developed against cardiovascular disease. On the website of Grindex it also says the drug "improves exercise performance and brain function of cardiac patients and healthy people."

Growth in the use of meldonium, particularly among Eastern European athletes, was a subject of the latest documentary from the German network ARD, which first reported on systematic Russian doping in 2014. The investigation cited a 2015 Russian study that found meldonium in 17% (724 of 4,316) of urine samples from Russian athletes tested. A global study found 2.2% of athletes had it in their system.

Growth in the use of meldonium, particularly among Eastern European athletes, was a subject of the latest documentary from the German network ARD, which first reported on systematic Russian doping in 2014. The investigation cited a 2015 Russian study that found meldonium in 17% (724 of 4,316) of urine samples from Russian athletes tested. A global study found 2.2% of athletes had it in their system.

A study of last year’s European Games in Baku, Azerbaijan, published Wednesday in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, found an “alarmingly high prevalence of meldonium use by athletes.” According to the study, 13 winners or medalists were taking meldonium, and 66 athletes tested positive for it.

Maria Sharapova of Russia, a five-time Grand Slam winner, said that she had tested positive for the banned drug meldonium during the Australian Open. Sharapova, a five-time Grand Slam winner, announced Monday that she had tested positive for meldonium during the Australian Open in January, shocking the tennis world and prompting a swift response by a number of her sponsors.

Created as a treatment for heart conditions in 1975, meldonium is widely available from Russian pharmacies without a prescription, selling for $3 to $10 for about 40 capsules. It can also be  purchased online. Meldonium is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for sale in the United States, where Sharapova has been based since she was 7. The Russian tennis federation said its doctors had not known she was taking meldonium.

purchased online. Meldonium is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for sale in the United States, where Sharapova has been based since she was 7. The Russian tennis federation said its doctors had not known she was taking meldonium.

Women’s tennis has always been a popular sport for both men and women alike. The sport combines strength and athleticism with speed, flexibility, and an element of grace that makes the players attractive and pleasing to the eye. Off the court, some of the sports biggest stars, and even some lesser players, have been targets of many photographers looking to capture their beauty and reveal just how hot they really are.

Most of these stunning beauties of the hardcourt are from the modern era as Russian and Eastern European bombshells made their way into the sport during the early 2000s. Maria Sharapova and Anna Kournikova (pictures) being two of them.

FOX SPORTS: Almost 100 athletes have tested positive this year for meldonium, the newly-banned drug that is threatening to keep the world’s highest-paid female athlete, Maria Sharapova, off the tennis court for years and has caused worldwide controversy in both Sharapova’s sport and throughout the sports world.

FOX SPORTS: Almost 100 athletes have tested positive this year for meldonium, the newly-banned drug that is threatening to keep the world’s highest-paid female athlete, Maria Sharapova, off the tennis court for years and has caused worldwide controversy in both Sharapova’s sport and throughout the sports world.

Early in the week, when we were still learning about Sharapova’s positive test and the drug that caused it, there were reports of seven other failed tests, from a wide variety of countries including Sweden, Ethiopia, Ukraine and, predominantly, Russia. But now with the new report that 99 positive tests (a number that’s rapidly growing) have happened in the first 69 days of the year, everything has changed.

On March , the widely held perception was that sports had seven drug cheats who refused to obey the rules to gain an advantage. How could Maria Sharapova possibly not know the new drug-testing rules? She’s either stupid or a liar, and since Sharapova has shown herself to be nothing but smart and savvy during her 12 years in the worldwide spotlight, she must have knowingly taken an illegal drug, right?

But now that there’s 99 positive tests, the tenor of the situation has changed. The problem is no longer isolated. Yes, this appears to be a Russian problem, but something is amiss. When asked if he was surprised by the high number of athletes who have been caught since the ban, David Howman, WADA’s director general, said, “We are not really at any stage surprised when a substance is put on the list and all of the sudden there are positive cases.”

Howman later told Clarey that he doesn’t believe negligence by athletes is the excuse for the rash of positive tests. But of course that’s what WADA would say. Anything else would make themselves look incompetent.

That’s what I’m not so sure negligence isn’t the answer. Should these athletes have known about the rule? Absolutely. Did they? Well, you may disagree, but ask yourself which scenario is more likely:

1) Ninety-nine separate people (and counting) made the conscious decision to keep cheating even though they knew their drug of choice was newly illegal and that a positive test could trigger a four-year ban.

2) Ninety-nine people didn’t get the memo or were unaware that the drug they were taking contained meldonium.

Which makes more sense to you, in general? (It’s naive to say some of the 99 weren’t simply continuing their drug cycle with full knowledge of its illegality.)

When it comes to athletes, money and drugs, one can’t help be a cynic. That tennis never had a major doping scandal involving a big player was laughable. It’s a sport that relies on endurance and recovery, exactly the attributes of doping’s “biggest” sport, cycling. Don’t tell me some of the best players didn’t use PEDs to stay on top or that lesser players didn’t to gain the smallest of advantages.

So what to do now? What should happen to Sharapova for getting caught taking a drug that seemed to be as popular in Russia as Gatorade is in the States?

So what to do now? What should happen to Sharapova for getting caught taking a drug that seemed to be as popular in Russia as Gatorade is in the States?

First, let’s dismiss the idea that all these athletes were “doping” before Jan. 1 or that Russia is somehow like East Germany because its athletes were taking meldonium. That’s insulting and preposterous. For whatever benefits or uses meldonium has in the real world, the athletes were taking a legal substance to enhance their performance. That it later became illegal doesn’t allow for moral judgments about taking it when it wasn’t.

Every athlete uses multiple performance enhancers in a single day. They take anti-inflammatory drugs, use supplements, drink specific concoctions made by trainers to help with recovery, spend hours with the trainer, take an ice bath, use a TENS machine or rest inside a pressurized sleep pod that mimics short-term hypoxia. And that’s just a few. If a supplement or a sleeping pod is banned tomorrow, does that make its users guilty today? Of course not. That’s why it’s so hard to clutch at my pearls at the thought of athletes taking a legal drug to be better at a sport. I just don’t care.

What I do care about is why 99 athletes have been caught since Jan 1. It’s back to the question of negligence. Whatever the story is -- that 99 athletes defied warnings and got caught, that 99 athletes knowingly cheated with a drug they knew would be a top priority for testers this year, or a combination of both -- it’s clear the doping testing system continues to be flawed.

What I do care about is why 99 athletes have been caught since Jan 1. It’s back to the question of negligence. Whatever the story is -- that 99 athletes defied warnings and got caught, that 99 athletes knowingly cheated with a drug they knew would be a top priority for testers this year, or a combination of both -- it’s clear the doping testing system continues to be flawed.

That’s why WADA needs an overhaul when it bans new drugs. First, the organisation should have been alerting athletes in 2015 if they were testing positive for a drug that would be banned in 2016. It should also give a 3-6 month grace period at the start of the year where the drug is illegal on a provisional basis so the same warning can be given. Because, honestly, if it was legal for 25 years, what’s another three months going to hurt?

For all the talk and self-defense by WADA about how it the ban on meldonium (which most athletes knew as mildronate) was clear, it evidently wasn’t. The PGA made a rule change about a putting stroke and gave golfers two-and-a-half years heads up. WADA makes a decision that holds an athlete’s future in the balance and the information was available only if you went to find it.

Players should have read the new rules. Someone like Sharapova, who travels with her own physio, certainly should have had a member of her team be an expert on drug testing, especially if she was taking a drug she knew wasn’t legal in the United States. This was the athlete’s responsibility, which means none of them are innocent parties. At best, they experienced willful ignorance or illegal defiance.

B ut given the current state of affairs, with athletes all over the spectrum testing positive for a drug that was legal one day and not the next, WADA deserves some, if not most, of the fault. The agency tasked with making sports fair failed in its mission. The point of WADA isn’t to entrap athletes for taking performance enhancers, it’s to ensure that all athletes are on a level playing field. On Jan. 1, WADA began tilting that field and it’s only now starting to get back into balance.

ut given the current state of affairs, with athletes all over the spectrum testing positive for a drug that was legal one day and not the next, WADA deserves some, if not most, of the fault. The agency tasked with making sports fair failed in its mission. The point of WADA isn’t to entrap athletes for taking performance enhancers, it’s to ensure that all athletes are on a level playing field. On Jan. 1, WADA began tilting that field and it’s only now starting to get back into balance.

Putin, “Russian athletes are not alerted to ban meldonium.” Russian President Putin has anti-doping agency WADA blamed for meldonium use of Russian athletes. According to him, there was insufficient warning that the drug is prohibited from 1 January.

Hans B. Skaset: In 1980, the international sports organisations were presented with a real opportunity to control the doping phenomena and limit the hysteria surrounding prize money and sponsorship. This chance was completely missed. Since then, sports leaders' chances of affecting the development of doping in sport have altered dramatically.

On the fringes of today's elite sport are many people and interests connected to the media, sponsors, competitors and arrangers as well as "consultants" of all categories. Top sport, - that is, sport of a real international nature is part of the "free market".

The pursuit of the best performance continues

Despite boasting branches in up to 200 nations, the 35 Olympic sporting associations and approximately 30 other non-Olympic organisations do not have the capacity, the will or even the opportunity to prevent ingrained doping practices. The search for performance-enhancing resources and methods will continue. This is sport's "cast iron law".

Entertainment value, and all the prestige and money that goes with it, is today linked directly and inseparably to the "presentation", or level of performance. No one buys or pays to view "out of date" performances, regardless of the presence of morally incorrupt and thoroughly healthy competitors.

With varying motives, official and semi-official national sports organizations have allowed themselves to submit to an IOC-dominated anti doping-organisation, the World Anti Doping Agency, or WADA. A majority of these national representatives know little about either the system of power in sport or a doping problem which they themselves have become partly responsible for.

Furthermore, many countries' political leaders cannot afford to let WADA function successfully. Most leading states have strong interests in top sport. Regular disclosures regarding doping are, therefore, not an attractive option. This is the IOC's trump card. The participation of states reduces the IOC's economic and political costs, while at the same time, through "staged disclosures", ensuring that the "show goes on".

N ationalism

ationalism

Doping at the L.A. Summer Games

Steroid use by athletes was already widespread in the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, but the public hadn't noticed yet.

Back then, insiders and athletes already knew that doping had saturated the international sports scene. Fans, though, were still largely in the dark.

And they would remain that way for a while because, as was later revealed, a number of positive test results from the Los Angeles Games were discarded, the alleged cheating kept secret for a decade

Carl Lewis has broken his silence on allegations that he was the beneficiary of a drugs cover-up, admitting he had tested positive for banned substances but claiming he was just one of "hundreds" of American athletes who were allowed to escape bans.

"There were hundreds of people getting off," he said. "Everyone was treated the same."

Lewis has now acknowledged that he failed three tests during the 1988 US Olympic trials, which under international rules at the time should have prevented him from competing in the Seoul games two months later.

The admission is a further embarrassment for the United States Olympic Committee, which had initially denied claims that 114 positive tests between 1988 and 2000 were covered up. It will add weight to calls by leading anti-doping officials and top athletes for an independent inquiry into the US's record on drug issues.