We hear all too often that the amount of processed food in your diet is unimportant for body composition as long as your caloric, macros (particularly protein), and fiber are all balanced. Is this accurate, however, in terms of how such a diet affects your regular calorie intake and ad libitum food consumption?

The diet conflicts have heated up. Obesity is blamed on a variety of factors, including fat, carbohydrates, sugar, processed foods, animal products, and so on. In terms of delivering a solution, the battleground outcome of carbs vs fat is the least promising at the population level.

At the group level, differences in low fat versus low carb therapies are clinically inconsequential (but they do matter for individuals). This is only one of many fruitless attempts to locate a "smoking gun" to explain the obesity epidemic. Multi-variable therapies outperform single-variable interventions when it comes to weight loss.

There is a firing squad of mechanisms causing weight increase, rather than a smoking gun. Researchers looked at a variety of pathways connected to energy consumption and body composition change in a recent study that included a brief investigation of processed meals as a contributor to weight gain. Researchers employed a free-eating model in a closely controlled metabolic ward study that resembled real-life conditions.

For two weeks, 20 adults were given meals that were dominated by processed or unprocessed foods, and the diets were matched for energy, macronutrients, sugar, fat, and fiber.

The subjects, on the other hand, were free to eat as much of the food as they wanted. Participants on the processed diet ate quicker and consumed more energy, ingesting more carbs and fat but similar protein to those on the unprocessed diet; as a result, they gained weight and fat mass on the processed diet while losing weight and fat mass on the unprocessed diet. Additionally, hunger hormone indicators were lower on the unprocessed diet than on the processed diet, and satiety was higher on the unprocessed diet than on the processed diet.

Participants ate 500kcal per day more on the processed diet than on the unprocessed diet, increasing body mass and fat mass from baseline, while losing body mass and fat mass on the unprocessed diet. At lunch and breakfast, more carbohydrate and fat were taken, absolute protein intake remained consistent, and both diets had equal energy densities. Specific foods, on the other hand, had a higher energy density, which the researchers tried to manage (albeit poorly due to the use of liquid) by dissolving fiber in processed diet beverages.

During the unprocessed diet, participants ate processed items faster, and the satiety hormone PYY increased while the hunger hormone ghrelin decreased. PYY was also considerably greater in the raw diet than in the processed diet. Processed meals are therefore consumed in excess for a variety of reasons: they are devoured faster, suppress hunger less, and require more energy to acquire a same protein and food mass – all of which have been found to regulate energy intake – as unprocessed foods.

Because processed meals have a lower protein content per calorie and a higher energy density, they are less satisfying, easier to consume fast, and more likely to result in higher overall calorie consumption.

While less common these days, there was a time in the "evidence-based IIFYM (if it fits your macros) community" when any questioning of certain foods being "acceptable" for health, fitness, fat loss, or bodybuilding would be met with a statement along the lines of: "diet quality doesn't matter for body composition change if macros (mainly protein), calories, fiber, and (depending on who was talking) sugar (depending on who was talking) are matched This is, for the most part, and at least in the short run, factually correct. I can think of odd diets in which some critical fatty acids, amino acids, and minerals are deficient and cause difficulties, but I digress.

Flexible dieting tracking can be a useful tool, but it should only be used for a limited time because there are risks to relying solely on external cues to regulate calorie intake. In my experience, the majority of gym-goers find tracking tedious and unsustainable in the real world. Thus, unless your aim isn't meant to be long-term (for example, contest prep leading to stage leanness), the habits you use shouldn't be, either, and 99 percent of individuals aren't going to watch their macros for the rest of their life. Is it important to know that a processed diet can be just as successful as an unprocessed diet if all nutritional variables such as calories and macros are kept under control?

Not really, because those variables are rarely controlled in practice. The only time I can imagine that statement being useful is if you're talking to someone who is truly terrified of certain processed meals and believes that they are hazardous at any frequency or dose for some sinister magical reason. In that instance, I might see the usefulness in informing someone that eating a Reese’s cup every now and again as part of a healthy diet is perfectly OK.

Even if someone does track their food on a regular basis, knowing that a processed diet can work isn't particularly useful. Indeed, following such a diet would increase the qualitative difficulty of maintaining a deficit with a processed food, which could pose complications. If people experience the same level of fullness and hunger after eating an extra 500 calories, it's reasonable to suppose they'd feel hungrier on a processed diet after consuming the same number of calories as they would on an unprocessed diet.

A phenomenon known as protein leverage hypothesis is another reason why processed diets lead to food overconsumption in the real world. Simply said, until a specific threshold of protein is consumed in an ad libitum scenario, satiety is lower and hunger is higher. As a result, because processed meals are so high in carbohydrates and fat, you'll need to consume more total calories to get the same amount of protein. Indeed, according to some studies, processed foods are fatty in part because they offer proportionally less protein per calorie.

In this study, it appears that the participants' ad libitum intake during the processed diet was primarily through carbohydrate- and fat-dominant foods, but there was a remarkably tight ad libitum intake of protein during both diets; because the participants ate more carbs and fats while eating the processed diet to achieve the same protein intake, more total calories were consumed. In fact, I believe that disparities in calorie density, fiber, and protein in the actual world would amplify this effect.

Yes, I believe the 500kcal difference reported in this study is a conservative estimate of the genuine difference in the real world, because there aren't researchers aiming to match the calorie density, protein, and fiber intakes of what's offered to you in the real world. Furthermore, while the processed food was not perceived to be more appealing, pleasant, or fulfilling, it was consumed more quickly, and physiological responses showed less satiation and increased hunger on the processed diet.

Another noteworthy discovery was that, while increases in body fat were the only significant changes in body composition, changes in lean mass were virtually as significant. The unprocessed diet resulted in a nonsignificant, tiny decrease in lean mass, while the processed diet resulted in a little increase. However, because adipose tissue is not entirely made up of fat mass and contains some lean tissue, there is an unavoidable loss or gain of lean mass when fat mass fluctuates.

Furthermore, changes in lean mass were substantially related with variations in sodium consumption, implying that extracellular fluid shifts manifested themselves as lean tissue alterations, contributing to this result.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

1. Processed diets resulted in considerable increases in energy consumption on an ad libitum basis. Participants in this study reported the same amount of hunger and satiation on both diets, although eating 500kcal more on the processed diet, and increased body fat on the processed diet.

2. This is due to a combination of factors in processed diets: they have a higher energy density, less protein per calorie, less fiber per calorie, are more likely to be consumed rapidly, and hence are less satiating. Also, processed foods are less expensive than unprocessed meals for the same amount of calories, however this wasn't taken into account in the study's findings.

3. Unprocessed, whole food diets, on the other hand, result in large reductions in energy consumption and, as a result, fat loss. This is related to reduced energy density, higher protein per calorie, higher fiber per calorie, slower eating periods, and, as a result, higher satiation. The disadvantage is that whole food is more costly.

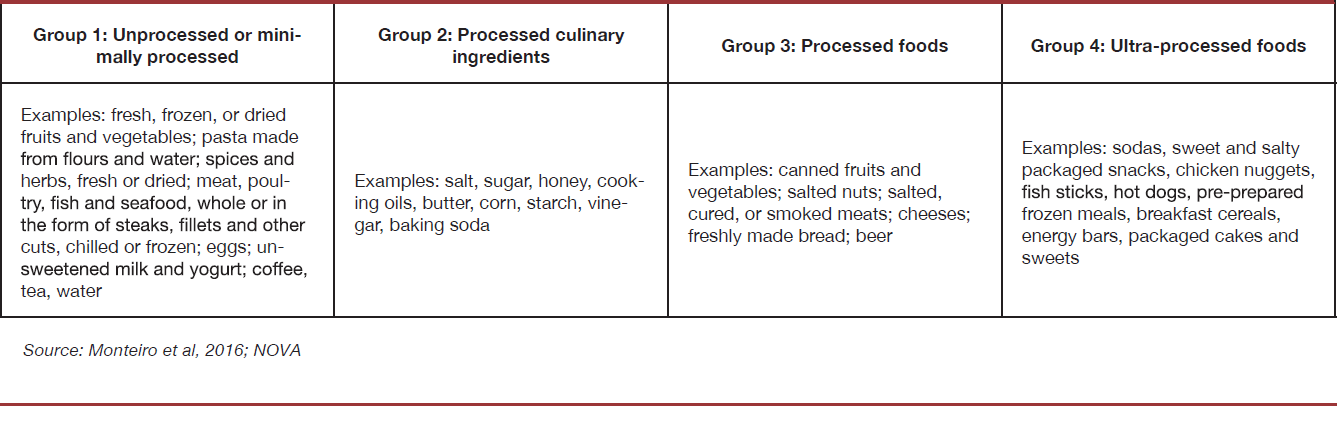

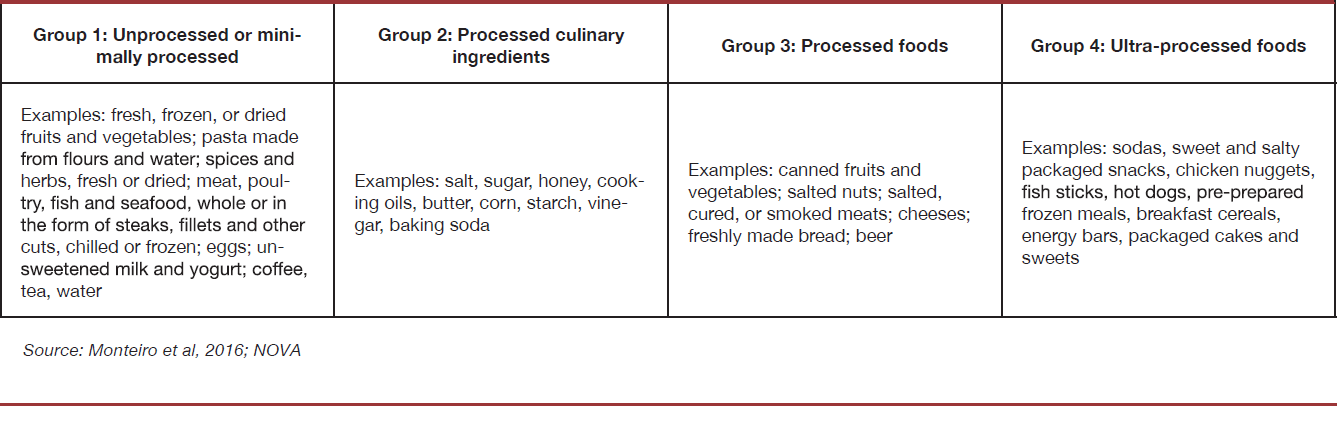

4. As a last point, Table 1 with the NOVA classification system can aid with application by giving you a clearer concept of how processed and unprocessed foods are classified.

References

1. Hall KD, Ayuketah A, Brychta R, Cai H, Cassimatis T, Chen KY, Chung ST, Costa E, Courville A, Darcey V, Fletcher LA. Ultra-Processed Diets Cause Excess Calorie Intake and Weight Gain: An Inpatient Randomized Controlled Trial of Ad Libitum Food Intake. Cell metabolism. 2019 May 16.

2. Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Levy RB, Moubarac JC, Louzada ML, Rauber F, Khandpur N, Cediel G, Neri D, Martinez-Steele E, Baraldi LG. Ultra-processed foods: what they are and how to identify them. Public health nutrition. 2019 Apr;22(5):936-41.

3. DellaValle DM, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. Does the consumption of caloric and non-caloric beverages with a meal affect energy intake? Appetite. 2005 Apr 1;44(2):187-93.

4. Steele EM, Raubenheimer D, Simpson SJ, Baraldi LG, Monteiro CA. Ultra processed foods, protein leverage and energy intake in the USA. Public health nutrition. 2018 Jan;21(1):114-24.

5. Barr S, Wright J. Postprandial energy expenditure in whole-food and processed food meals: implications for daily energy expenditure. Food & nutrition research. 2010 Jan 1;54(1):5144.

6. Levine JA, Eberhardt NL, Jensen MD. Role of nonexercise activity thermogenesis in resistance to fat gain in humans. Science. 1999 Jan 8;283(5399):212-4.

7. Abe T, Dankel SJ, Loenneke JP. Body Fat Loss Automatically Reduces Lean Mass by Changing the Fat-Free Component of Adipose Tissue. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.). 2019 Mar;27(3):357.

8. Hall KD, Guyenet SJ, Leibel RL. The carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity is difficult to reconcile with current evidence. JAMA internal medicine. 2018 Aug 1;178(8):1103-5.

9. Hall KD, Guo J. Obesity energetics: body weight regulation and the effects of diet composition. Gastroenterology. 2017 May 1;152(7):1718-27.