Alcohol and Muscle Recovery

Nowadays alcohol consumption in western countries is considerably increasing. Also after sport events and not only the public drinks, the athletes themselves like to drink to victory.

You’ve probably heard that alcohol calories will make you fat and that beer causes beer bellies. You may have heard that alcohol consumption negatively affects your metabolism and testosterone production, or even that it hampers protein synthesis.

Most of the misinformation surrounding the negative effects of alcohol are exaggerated, over-exaggerated or just plain wrong. Lots of these information comes from the authorities themselves or from the anti-drug campaigners (paid by the same authorities). Don’t forget the health freak bloggers and many fitness and mainstream media. Scaremongering probably sells.

Let’s put it all in perspective, an old saying goes “It’s the dose that makes the poison.” If you read scientific studies, be aware of the sometime huge doses. And it’s not possible to extrapolate results in rat studies or “in vivo” studies one in one to humans. Everyone knows that binge drinking for weeks is worse for you than moderate alcohol drinking.

Let’s put it all in perspective, an old saying goes “It’s the dose that makes the poison.” If you read scientific studies, be aware of the sometime huge doses. And it’s not possible to extrapolate results in rat studies or “in vivo” studies one in one to humans. Everyone knows that binge drinking for weeks is worse for you than moderate alcohol drinking.

Everyone picks his own poison, but some take them all. We are fully aware of the real hard-core guys that live the day like there is no tomorrow. If they use steroids they think in grammes instead of milligrams. And they use all kind of ergogenic drugs and recreational drugs at the same time, just read some stories written by Craig Titus or Nasser El Sonbatty. But that is not the reality for most bodybuilders and recreational bodybuilders/fitness enthusiasts. So if you are a natural bodybuilder the amount of what you drink, when you drink and what you eat with it does matter and for those this blogpost can learn you something.

What does alcohol intake do to your endogenous Testosterone?

What does alcohol intake do to your endogenous Testosterone?

Bianco et al. 2014 Moderate doses of ethanol (0.83 g/kg) in resistance trained men when consumed immediately after exercise (where nothing was eaten 3.5 hours before, food given during drinking ab libitum) failed to note any significant differences in testosterone levels for up to 300 minutes after exercise and another sport related study using 1 g/kg after a simulated rugby match failed to note a decrease in testosterone despite noting a reduction in power output. Rojdmark et al. did not pair ethanol with exercise but used a low dose of 0.45 g/kg on three separate pulses. 90 minutes apart noted that although there was a trend for testosterone to increase that did not differ between ethanol and water intake. Conversely, a slightly lower intake (0.5 g/kg) has been shown to actually increase circulating testosterone from 13.6 nmol/L to 16 nmol/L.

Around the 1.5 g/kg or higher ethanol intake, it appears that a dose-dependent decrease of testosterone occurs and appears to occur with some degree of time delay up to 10 hours after consumption. However, the acute intake of ethanol of about 1.5 g/kg suppresses the production of testosterone within one hour through a decrease in Luteinizing hormone (LH) release.

Hormonal levels of testosterone have also been measured after heavy resistance exercise. Participants consumed either 1.09 g/kg of grain ethanol per kilogram lean mass (EtOH group) or no ethanol post exercise (placebo group). Peak blood ethanol concentration (0.09 ± 0.02 g·dL) was reached within 60–90 min post exercise. Total testosterone and free testosterone were elevated significantly immediately after exercise in both groups. At 140–300 min post exercise, total testosterone and free testosterone levels as well as free androgen index were significantly higher only in the EtOH group. The study demonstrated that during the recovery period from heavy resistance exercise, post exercise ethanol ingestion affects the hormonal profile including testosterone concentrations and bioavailability.

How Much

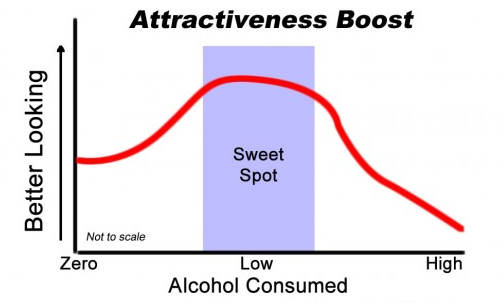

Let me explain how much you can use. In the above study 1 gram ethanol (alcohol) per kilogram bodyweight (1g/kg) increased testosterone a little bit. 0.5 g/kg really increased total testosterone and free testosterone. At 1.5 g/kg alcohol suppresses total and free testosterone. So the sweet spot lies between 0.5 – 1 g/kg.

In the United States, according the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the average "standard" alcoholic drink (4-5oz wine, 12oz beer, 1.5oz spirits) drink contains roughly 14 grams of pure alcohol.

In Europe a standard glass of beer of 5% (250cc), wine of 12% (100cc) and spirits of 35% (35cc) all contain the same amount of pure alcohol (about 10 grams).

In Europe a standard glass of beer of 5% (250cc), wine of 12% (100cc) and spirits of 35% (35cc) all contain the same amount of pure alcohol (about 10 grams).

A 100 kg (220 lbs.) bodybuilder that consumes 1g/kg (1g/2.2 lbs.) consumes 100 gram alcohol, which is 7 drinks in the USA and 10 in Europe, makes sense?? Eeehm gimme 10..

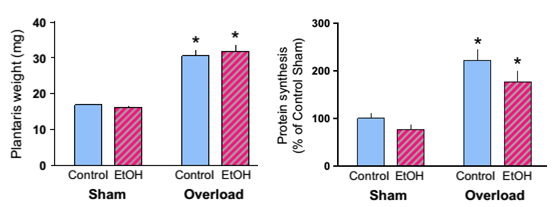

Steiner et al 2015 "Moderate alcohol consumption does not impair overload‐induced muscle hypertrophy and protein synthesis."

When the scientists removed the plantaris muscle from the sham and overload leg after 14 days, they found no difference in body weight between Con and EtOH-fed mice. More specifically, the muscle weight of the plantaris muscle of both groups increased by 90%, the protein synthesis by 125% (the non-significant inter-group differences can be ignored, because studies show that post-exercise protein synthesis and actual muscle gains don't correlate in humans beings and the same can be safely assumed for mice (Mitchell. 2014).

It's easy to see that the alcohol intake did not inhibit the increase in skeletal muscle weight (left) and the decrease in protein synthesis was not statistically significant (right | Steiner. 2015). It should be mentioned, though, that the model the scientists used (mice) does not translate 1:1 to human beings. The dosed used was 3g/kg, which according to this, would be around 0.25g/kg in humans.

Similarly, the overload-induced increase in signaling proteins like mTOR (Ser2448), 4E-BP1 (Thr37/46), S6K1 (Thr389), rpS6 (Ser240/244), and eEF2 (Thr56) were comparable in muscle from Con and EtOH mice. The only thing that differed and may indicate that you could see different results in the long-term is the fact that ULK1, p62, and LC3, three markers of autophagy, i.e. self-programmed cell death were elevated in the muscle of the "binging" mice.

“In summary, moderate alcohol consumption did not alter muscle hypertrophy, protein synthesis, or the majority of mTORC1-related signaling events induced by 14 days of chronic muscle overload. These findings are relevant to patients with chronic alcohol-induced muscle disease as they indicate that a simple intervention such as daily weightlifting exercise could provide a sufficient anabolic stimulus to induce muscle (re)growth and potentially reverse or prevent further disease.” And what if during this study anabolic androgenic steroids and/or hGH would have been used?

Alcohol ingestion impairs maximal post-exercise rates

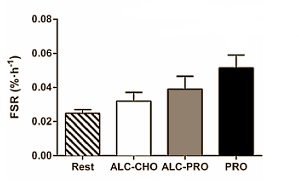

T he culture in many team sports involves consumption of large amounts of alcohol after training/competition. The effect of such a practice on recovery processes underlying protein turnover in human skeletal muscle are unknown. Parr et al 2014 determined the effect of alcohol intake on rates of myofibrillar protein synthesis (MPS) following strenuous exercise with carbohydrate (CHO) or protein ingestion.

he culture in many team sports involves consumption of large amounts of alcohol after training/competition. The effect of such a practice on recovery processes underlying protein turnover in human skeletal muscle are unknown. Parr et al 2014 determined the effect of alcohol intake on rates of myofibrillar protein synthesis (MPS) following strenuous exercise with carbohydrate (CHO) or protein ingestion.

If you drink alcohol after a training session it gets in the way of the anabolic processes taking place. Drinking a protein shake after the training session reduces this damage, but doesn’t get rid of it completely.

Nevertheless, a lot of athletes drink alcohol after training.

The researchers were curious to know to what extent post-workout whey and carbohydrates supplementation could help to cancel out the anti-anabolic effect of alcohol.

The researchers got eight active men to do strength training leg exercises and then several cardio sessions on a cyclometer. The researchers put the cardio sessions together in such a way that the total workout model allowed for all imaginable types of training regimes.

An hour after finishing their training the men drank the equivalent of 12 units of alcohol!! On one occasion the subjects were given 25 g maltodextrin after their workout, and 25 g maltodextrin four hours after the workout, when they had stopped drinking.

O n another occasion the subjects were given two 25-g doses of whey instead of maltodextrin.

n another occasion the subjects were given two 25-g doses of whey instead of maltodextrin.

Alcohol inhibited protein synthesis, the researchers observed when they examined samples of the men’s muscle fibre. Whey [ALC-PRO] reduced this effect, but was not capable of restoring muscle fibre synthesis to the level achieved by drinking a whey shake but not drinking alcohol after training [PRO].

Post-training alcohol consumption had virtually no effect on the amount of amino acids that reached the muscle cells. What it did do was to reduce the activity of anabolic signaling molecules like mTOR and p70S6K in the muscle cells.

“In conclusion, the current data provide the novel observation that alcohol impairs the response of muscle protein synthesis in exercise recovery in human skeletal muscle despite optimal nutrient provision”, the researchers write. “The quantity of alcohol consumed in the current study was based on amounts reported during binge drinking by athletes.”

“We propose our data is of paramount interest to athletes and coaches. Our findings provide an evidence-base for a message of moderation in alcohol intake to promote recovery after exercise with the potential to alter current sports culture and athlete practices.”

Most meals decrease the absorption rate and increases the elimination rate of alcohol. The result? The percentage of bioavailable alcohol that actually reaches your blood drops to around 70% for most meals. High protein meals are particularly effective at stimulating the liver and delaying gastric emptying. They can reduce alcohol’s bioavailability to under 40%.

Aerobic Performance

Earlier studies found no significant consequence of alcohol on a sub-maximal endurance performance and a 5-mile treadmill time trial respectively. Contrastingly and not surprisingly, there is also literature that demonstrates that alcohol is detrimental to endurance performance.

W hat is apparent is that a threshold exists at which point alcohol becomes detriment to aerobic performance.

hat is apparent is that a threshold exists at which point alcohol becomes detriment to aerobic performance.

Anaerobic Performance

Despite the long list of skeletal muscle and neurological symptomatology associated with alcohol consumption, the majority of literature has been unable to establish a significant cause-effect relationship between alcohol and anaerobic performance. To the reviewers knowledge McNaughton and Pierce have conducted the only research that has identified an effect of alcohol on sprint performance. This research examined five sprinters using sprint time as a measure of performance and established a detrimental, albeit inconsistent, association between alcohol dosage and sprint performance. Alcohol was ingested immediately prior to exercise testing so this data is limited to the acute effects of alcohol intoxication and does not apply to more chronic hangover symptoms.

Recent research has been unable to validate these findings, and have consistently seen no change in strength or power characteristics following acute alcohol ingestion.

Vella et al 2010, Alcohol, Athletic Performance and Recovery

How Does Beer and Wine Affect Fat Loss?

When we get into alcohol and fat loss, things get a bit tricky. In this realm we have to look at calories, endocrine effects (which impact muscle too) and the context in which alcohol is consumed.

Let's review what we already know. The biochemistry of alcohol metabolism says that it has a very high thermic effect, just like protein. It's also costly energetically for alcohol to be stored. When acetate and acetyl-coA build up, this shuts down burning of other fuels like carbs and fats. Studies support this. When carbs or fat are replaced calorie-for-calorie with alcohol, there's no fat storing effect. Some of the research even hints there may be a weight loss effect in the same way that subbing protein in place of fat and carbs might have.

Another thing we have to look at is how alcohol impacts food intake. This seems to be individualized with some suffering from a "disinhibition effect" and others not. By disinhibition I mean that people's natural control mechanisms to regulate the amount of food they eat is reduced. So, just as people become uninhibited when they drink and say all types of crazy stuff they wouldn't say sober, others can eat all kinds of food they may not eat when they're sober.

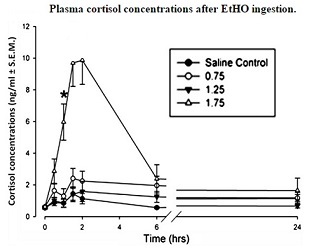

This impact on appetite may vary with the type of alcohol consumed too. There are a few rules here to know. Beer is bitter and bitter compounds release GLP-1, which is a hunger suppressing compound. Beer also seems to lower cortisol in the short run and in lower doses. Higher doses may have the reverse effect. This is important because we now know cortisol is involved in hunger and cravings, and switches off the motivation centers in the brain while amping up the reward centers. Isohumulones, which come from the female hop plant, are what give beer its bitter taste. They also give beer the (slight) ability to stimulate brown fat tissue, which resulted in a statistically significant reduction in visceral fat—the unhealthy kind of fat that surrounds our organs (study). So, surprisingly, beer has a compound in it that can actively combat beer bellies? Who knew!

This impact on appetite may vary with the type of alcohol consumed too. There are a few rules here to know. Beer is bitter and bitter compounds release GLP-1, which is a hunger suppressing compound. Beer also seems to lower cortisol in the short run and in lower doses. Higher doses may have the reverse effect. This is important because we now know cortisol is involved in hunger and cravings, and switches off the motivation centers in the brain while amping up the reward centers. Isohumulones, which come from the female hop plant, are what give beer its bitter taste. They also give beer the (slight) ability to stimulate brown fat tissue, which resulted in a statistically significant reduction in visceral fat—the unhealthy kind of fat that surrounds our organs (study). So, surprisingly, beer has a compound in it that can actively combat beer bellies? Who knew!

Red wine contains histamine which raises cortisol. So we assume this would mean increased appetite. Spirits and white wine have neither the bitter compounds or the histamine content of beer and red wine, so it would be difficult to speculate the effects.

Red wine contains histamine which raises cortisol. So we assume this would mean increased appetite. Spirits and white wine have neither the bitter compounds or the histamine content of beer and red wine, so it would be difficult to speculate the effects.

A study out of Kokavecet al 2009 shows exactly what we'd predict. Beer lowers cortisol and has a short-term appetite suppressing effect. Red wine raises cortisol fairly quickly and stimulates the appetite faster too. White wine was similar to beer. Spirits were not looked at in this study.

It does seem to be clear that any alcohol will raise cortisol eventually. The effects just seem to be time dependent in the case of beer, and impacted by amount as well. We now know cortisol has some impact on appetite, but it also plays a role in workout recovery. You don't want cortisol high in either scenario.

It does seem to be clear that any alcohol will raise cortisol eventually. The effects just seem to be time dependent in the case of beer, and impacted by amount as well. We now know cortisol has some impact on appetite, but it also plays a role in workout recovery. You don't want cortisol high in either scenario.

Alcohol: impact on sports performance and recovery in male athletes. Barnes 2014

Alcohol is the most commonly used recreational drug globally and its consumption, often in large volume, is deeply embedded in many aspects of Western society. Indeed, athletes are not exempt from the influence alcohol has on society; they often consume greater volumes of alcohol through bingeing behaviour compared with the general population, yet it is often expected and recommended that athletes abstain from alcohol to avoid the negative impact this drug may have on recovery and sporting performance. While this recommendation may seem sensible, the impact alcohol has on recovery and sports performance is complicated and depends on many factors, including the timing of alcohol consumption post-exercise, recovery time required before recommencing training/competition, injury status and dose of alcohol being consumed. In general, acute alcohol consumption, at the levels often consumed by athletes, may negatively alter normal immunoendocrine function, blood flow and protein synthesis so that recovery from skeletal muscle injury may be impaired. Other factors related to recovery, such as rehydration and glycogen resynthesis, may be affected to a lesser extent. Those responsible for the wellbeing of athletes, including the athlete themselves, should carefully monitor habitual alcohol consumption so that the generic negative health and social outcomes associated with heavy alcohol use are avoided. Additionally, if athletes are to consume alcohol after sport/exercise, a dose of approximately 0.5 g/kg body weight is unlikely to impact most aspects of recovery and may therefore be recommended if alcohol is to be consumed during this period.

E ffects of heavy episodic drinking on physical performance in club level rugby union players. Prentice et al 2015

ffects of heavy episodic drinking on physical performance in club level rugby union players. Prentice et al 2015

This study investigated the effects of acute alcohol consumption, in a natural setting, on exercise performance in the 2 days after the drinking episode. Additionally, alcohol related behaviours of this group of rugby players were identified.

Nineteen male club rugby players volunteered for this study. Measures of counter movement jump, maximal lower body strength, repeated sprint ability and hydration were made 2 days before and in the 2 days following heavy episodic alcohol consumption..

The reported alcohol consumption ranged from 6 to >20 standard drinks!! A significant decrease in sleep hours was reported after the drinking episode with participants reporting 1-3 h for the night. A significant reduction in counter movement jump the morning after the drinking episode was observed; no other measures were altered at any time point compared to baseline

Heavy episodic alcohol use, and associated reduced sleep hours, results in a reduction in lower body power output but no other measures of anaerobic performance the morning after a drinking session. Full recovery from this behavior is achieved by 2 days post drinking episode.

Want to Be More Attractive? Science Says Have a Drink.

G etting your business portrait photo taken? Meeting new people at a networking event? Here’s some counter-intuitive advice: consider having a drink. You may be seen as being more attractive.

etting your business portrait photo taken? Meeting new people at a networking event? Here’s some counter-intuitive advice: consider having a drink. You may be seen as being more attractive.

We’ve all heard expressions like “looking through beer goggles” that suggest other people look better after you’ve had a few drinks. Surprising research now shows that a little alcohol can make the drinker look better to others as well.

University of Bristol researchers conducted an experiment in which heterosexual individuals rated photos of an opposite-sex subject under two conditions. One photo was of the subject in a no-alcohol condition, and the other was of the subject after consuming a low or high dose of alcohol. Surprisingly, the “low dose” drinkers were judged to be better looking by the sober evaluators than their no-alcohol selves.

How Many Drinks Will Make YOU Look Good?

A lthough the shorthand for the doses tested is one drink (low dose) or two (high dose), that may be a bit misleading. Quite properly, the scientists varied the amount of alcohol based on the weight of the subject. The low dose condition was, for a 154 pound (70 kg) subject, 250 ml (8.5 oz) of 14% ABV wine. With a standard pour of wine in the 4-5 ounce range, that’s close to two glasses. The 14% alcohol content is a bit higher than most wines, too, with 13.5% being very common for both red and white wines.

lthough the shorthand for the doses tested is one drink (low dose) or two (high dose), that may be a bit misleading. Quite properly, the scientists varied the amount of alcohol based on the weight of the subject. The low dose condition was, for a 154 pound (70 kg) subject, 250 ml (8.5 oz) of 14% ABV wine. With a standard pour of wine in the 4-5 ounce range, that’s close to two glasses. The 14% alcohol content is a bit higher than most wines, too, with 13.5% being very common for both red and white wines.

Put another way, the low dose condition was one-third of a typical 750 ml bottle of wine for a person weighing 154 pounds (70 kg). The high dose condition that resulted in a photo rated as less attractive was two-thirds of a bottle.

So, people above that weight, the “low dose” is more like a couple of glasses of wine. Two typical beers or normal cocktails would provide a similar dose.

Smaller individuals might find that one drink is optimal for the appearance-boosting effect.

Suter 2005: There seems to be a large individual variability according to the absolute amount of alcohol consumed, the drinking frequency as well as genetic factors. Presently it can be said that alcohol calories count more in moderate nondaily consumers than in daily (heavy) consumers. Further, they count more in combination with a high-fat diet and in overweight and obese subjects.

Why are the harmful effects of alcohol so exaggerated?

We all know that consuming too much alcohol is bad for you, but the effects are truly highly exaggerated. It’s said that it will make you fat, increases your estradiol, resulting in man boobs. It hinders performance and halts muscle growth. Why mainstream media and fitness magazines report this, I don’t know. If you read the enormous amount of scientific studies you’ll soon learn it depends on a lot of factors, how toxic it is, if toxic at all. When do you drink, what did you eat before and after drinking, your gender, your BMI (fat percentage) etc etc.

We all know that consuming too much alcohol is bad for you, but the effects are truly highly exaggerated. It’s said that it will make you fat, increases your estradiol, resulting in man boobs. It hinders performance and halts muscle growth. Why mainstream media and fitness magazines report this, I don’t know. If you read the enormous amount of scientific studies you’ll soon learn it depends on a lot of factors, how toxic it is, if toxic at all. When do you drink, what did you eat before and after drinking, your gender, your BMI (fat percentage) etc etc.

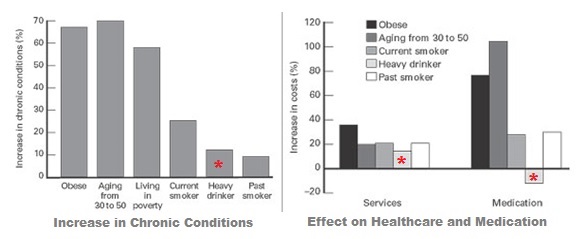

Mortality

Alcoholics are riddled with heart disease, health problems and higher rates of cancer. Abstainers though, surprisingly, have the next highest mortality rate. Moderate drinkers have been proven time and time again to live the longest (study, study, study, study), which is admittedly a little peculiar, since the mechanisms behind the supposed health benefits of alcohol aren’t well understood yet (although this study sheds some light on that). If you stick within light to moderate alcohol consumption (1-3 drinks per day) then you probably have nothing to worry about and can potentially collect on a bunch of health benefits, including a stronger immune system, a decreased chance of getting the common cold, Alzheimer’s, dementia, metabolic syndrome, cancer, arthritis, heart disease, and depression. (study, study, study, study, study, study, study, study) The absolute healthiest amount to drink is one drink per day, and the negative effects start to come after about 3.5 drinks per day.

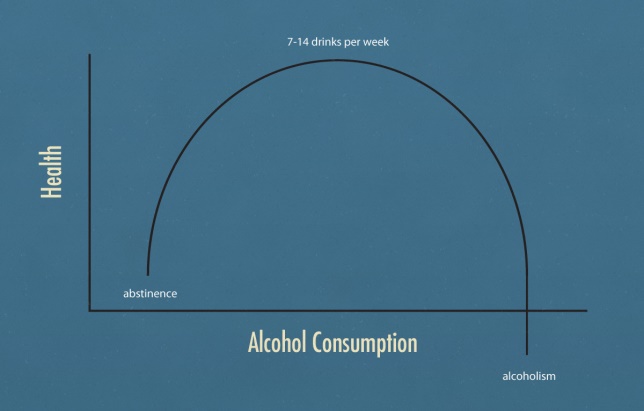

A classic inverted-U curve can be seen in the relationship between alcohol consumption and health. If you go from not drinking at all to drinking one glass of wine a week, you’ll live longer. And if you drink two glasses a week, you’ll live a little bit longer, and three glasses a little bit longer still – all the way up to about seven glasses a week. (These numbers are for men, not women.) That’s the upslope: the more, the merrier. Then there’s the stretch from, say, seven to fourteen glasses of wine a week. You’re not helping yourself by drinking more in that range. But you’re not particularly hurting yourself either. That’s the middle part of the curve. Finally, there’s the right side of the curve: the downslope. That’s when you get past fourteen glasses of wine a week and drinking more starts to leave you with a shorter life. Alcohol is not inherently good or bad or neutral. It starts out good, becomes neutral, and ends up bad.”

classic inverted-U curve can be seen in the relationship between alcohol consumption and health. If you go from not drinking at all to drinking one glass of wine a week, you’ll live longer. And if you drink two glasses a week, you’ll live a little bit longer, and three glasses a little bit longer still – all the way up to about seven glasses a week. (These numbers are for men, not women.) That’s the upslope: the more, the merrier. Then there’s the stretch from, say, seven to fourteen glasses of wine a week. You’re not helping yourself by drinking more in that range. But you’re not particularly hurting yourself either. That’s the middle part of the curve. Finally, there’s the right side of the curve: the downslope. That’s when you get past fourteen glasses of wine a week and drinking more starts to leave you with a shorter life. Alcohol is not inherently good or bad or neutral. It starts out good, becomes neutral, and ends up bad.”